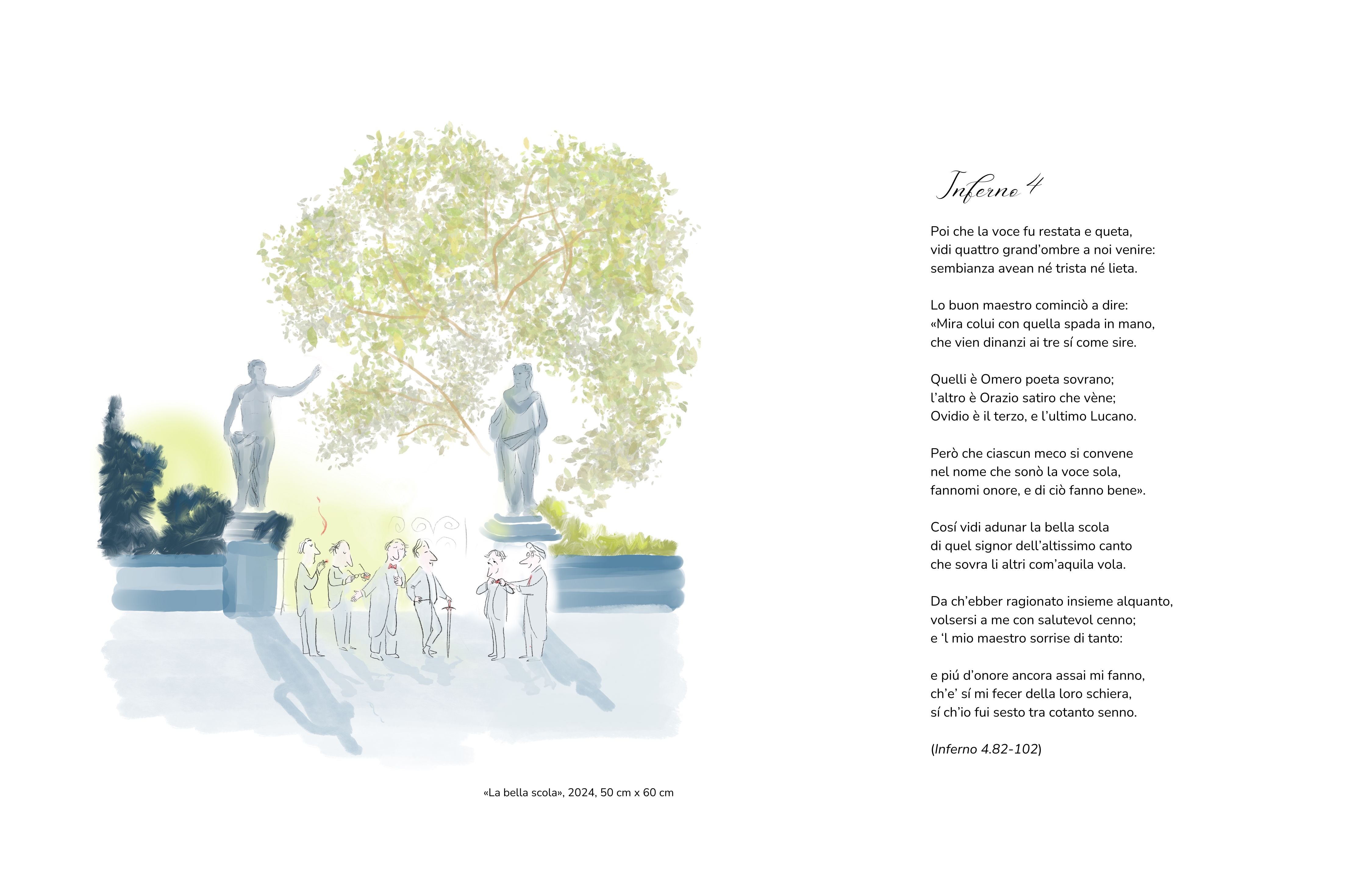

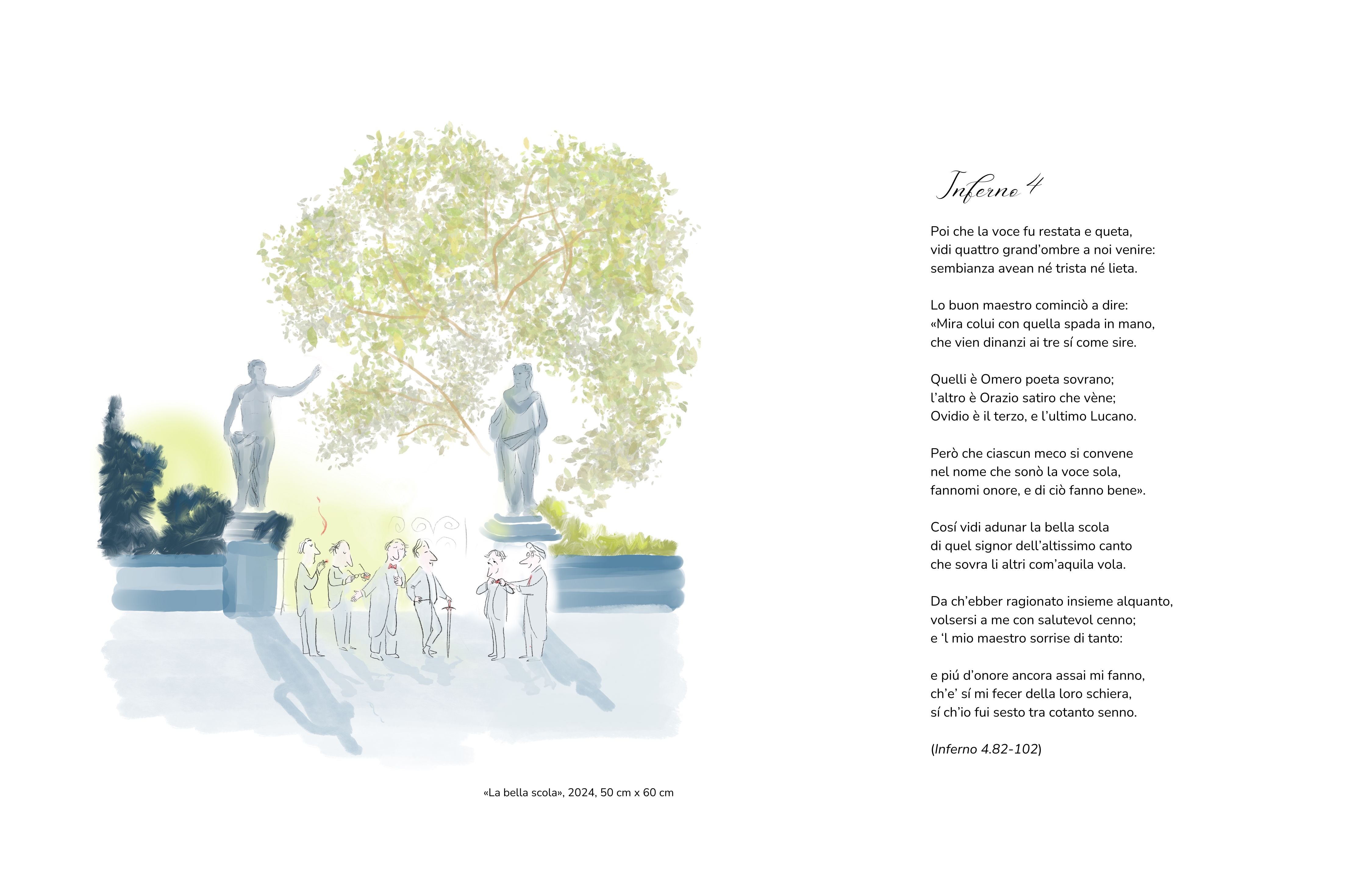

«La bella scola»

This composition captures the scene described by Dante in which he is greeted warmly by this esteemed group: "Da ch’ebber ragionato insieme alquanto, / volsersi a me con salutevol cenno; / e ‘l mio maestro sorrise di tanto" (Soon after they had talked a while together, / they turned to me, saluting cordially; / and having witnessed this, my master smiled;) [Inf. 4.97-99]. Dante is notably included as the sixth member of this illustrious company - “la bella scola” (the splendid school) [Inf. 4.94].

Pastel colours distinguish this scene from the preceding canto, where boldness pervades: "Non era lunga ancor la nostra via / di qua dal sonno, quand’io vidi un foco / ch’emisperio di tenebre vincía" (Our path had not gone far beyond the point / where I had slept, when I beheld a fire / win out against a hemisphere of shadows) [Inf. 4.67-69]. Set in "prato di fresca verdura" (a meadow of green flowering plants) [Inf. 4.111], the group of souls—referred to as "la selva… di spiriti spessi" (the wood … where many spirits thronged) [Inf. 4.66]—includes Homer, Horace, Ovid, and Lucan. Homer leads, “... con quella spada in mano” (with sword in hand) [Inf. 4.86], and the setting of the terrace symbolically reflects the notion of "Limbo" as the "border" or "hem.” The bold red colour of the sky from the artwork of Inferno 3 reappears in Inferno 4, but this time it's applied subtly, reappearing as accents in the characters’ clothing—whether in a tie, a cigarette, a handkerchief, or the hilt of a sword—creating connection between the characters in this canto based on affection.

In contrast to the faceless figures depicted in my artwork of Inferno 3, the characters in Inferno 4 are larger and depicted with distinct faces. This artistic choice conveys the honour these souls earned in life, which secured them divine recognition: "E quelli a me: ‘L’onorata nominanza / che di lor suona su nella tua vita, / grazia acquista nel ciel che sí li avanza.’" (And he to me: “The honour of their name, / which echoes up above within your life, / gains Heaven’s grace, and that advances them.”) [Inf. 4.76-78]

By rendering the faces of these figures, the artwork emphasises the concept of "nominanza" (honour) —the enduring fame of the virtuous pagans—aligning with the humanistic idea of fame (Barolini 16). This stands in contrast to the souls of Inferno 3, who all look the same, having taken a neutral stance in life.

Virgil is portrayed as proudly introducing Dante to the group, with his arm resting on Dante’s shoulder, symbolising the paternal bond between them. Additionally, the poets are portrayed as warm and congenial toward Dante. By depicting everyone in this amicable way, the artwork evokes a poignant concern in the viewer—namely, the perceived injustice that our beloved Virgil and these four esteemed poets, despite their sinlessness, have been denied entry into Paradise solely due to their birth "dinanzi al cristianesmo," [Inf. 4.37] before the advent of Christianity. We are left with the poignant realisation that Dante will ultimately leave them behind and will never be able to reciprocate their warm welcome in Heaven.

The two statues further emphasise the notion of honour: the male figure, depicted as a philosopher or orator with an outstretched arm, signifies the revered intellectuals, while the female statue represents women who were also spared from torment according to this Canto, such as Rachel, Electra, Penthesilea, Camilla, and Lavinia.

***

Divine Love vs Divine Justice:

Inferno 4 introduces the virtuous pagans who dwell in Limbo, the first circle of Hell. Although they experience "duol senza martìri" [Inf. 4.28], a sorrow without torment, they are denied the ascent to Paradise due to their lack of Baptismal grace, having been born before the time of Christ. Although they are sinless, they are left with the desire for salvation but devoid of any hope for it. Nevertheless, these souls are regarded with honour.

In Paradiso 19, Dante questions how it can be just to exclude a sinless person from Paradise simply because they are born either 1) before Christ or 2) after Christ, but in non-Christian lands and therefore without access to Christian texts. In Paradiso 19, Dante wrestles with what he perceives as divine injustice and reflects on his luck at not being born “da gente studiosa lontano” (far removed from the company of educated persons) [Conv. 1.1.4]. Ultimately, the eagle silences all doubt, reminding Dante and all humans that they are incapable of fully understanding or judging divine justice.

This exhibit explores Dante’s view of Divine Love. Is Divine Justice incompatible with Divine Love? How do we reconcile the two?

Love as Phileo:

The notion of Phileo as love (the φιλέω word family) was often used in the New Testament. Ann Graham Brock defines this notion of love: “In the ancient world φιλέω often denoted the love of friends, conveying a sense of preferential love and often implying a certain reciprocity. The first-century Christian communities could not have been immune to their environments, including the popularity of φίλος and φιλέω in their linguistic context. The noun φίλος ranged in nuances from "one who is a friend of," a "loved one," a "favourite," to a "follower" of a political leader. The plural of φίλος also often designated members of a philosophical or religious fellowship, such as the Pythagoreans and the Epicureans who called themselves "the friends."” (Brock)

With this understanding of love, could we not also recognize love in the relationship between Virgil and Dante, as well as among the six poets of “la bella scola” in Inferno 4?" Doesn't the pilgrim-Dante's distress over the injustice of the four poets being condemned to Limbo, despite their sinlessness, reflect his love and affection for his fellow poet-friends?"

———————————————————————————————————————————

Barolini, Teodolinda. “Inferno4: Non-Christians in the Christian Afterlife.”Commento Baroliniano, Digital Dante. New York, NY: Columbia University Libraries, 2018. https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/dante/divine-comedy/inferno/inferno-4/

Brock, Ann Graham. “The Significance of Phileō and Philos in the Tradition of Jesus Sayings and in the Early Christian Communities.” Harvard Theological Review, vol. 90, no. 4, Oct. 1997, pp. 393–409. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rfh&AN=ATLA0001004897&site=ehost-live.