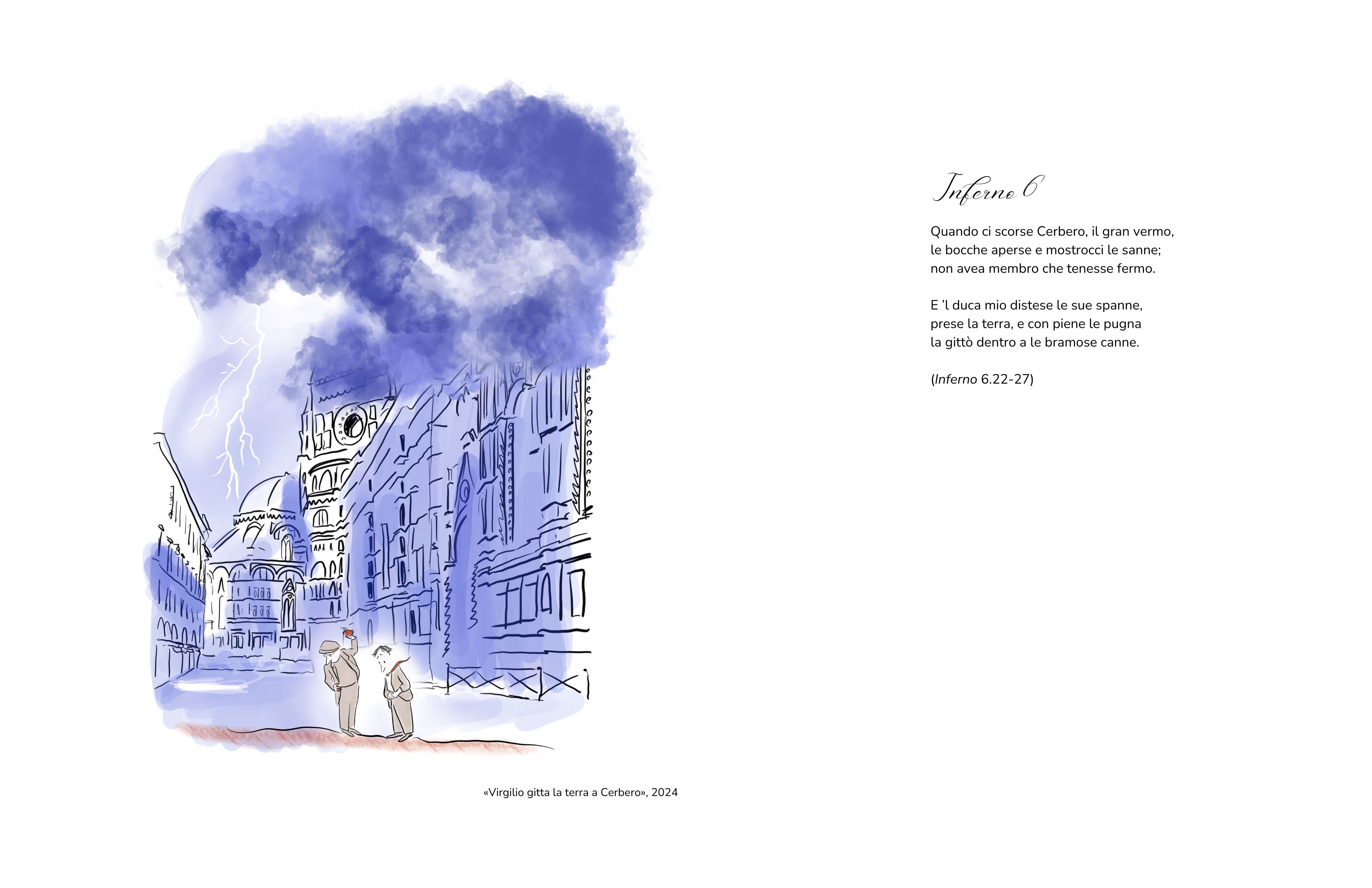

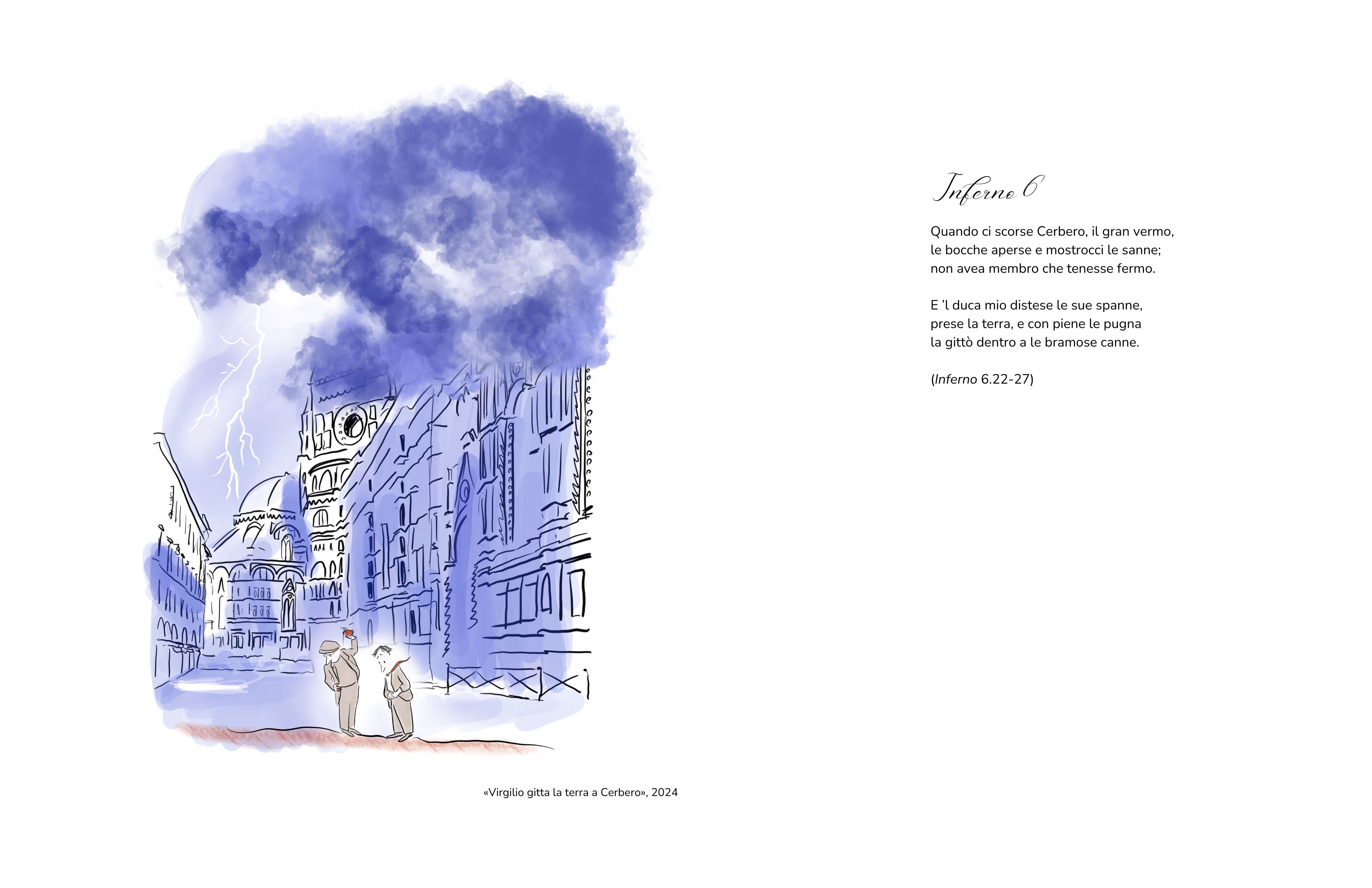

Commentary on Inferno 6

«Virgilio gitta la terra a Cerbero»

In Inferno 6, Virgil and Dante arrive in the third circle of hell which holds the gluttons. Upon their arrival, Virgil throws a fistful of earth into the “bramose canne” (famished jaws) [Inf.6.27] of the three-headed dog, Cerberus, who devours it. This scene is in homage to Book 6 of the Aeneid in which Virgil throws a honey cake at the three-headed guardian of the underworld (Barolini Inferno 6 9-10). However, Cerberus is not the main focus of this scene - Florence is! Even though the beginning of this canto depicts literal gluttony, Dante metaphorically accuses Florence of being gluttonous for dominion and power (Barolini Inferno 6 12).

Before Dante’s exile, Florence was under attack by factional rivals – the White Guelphs (pro-imperial), Black Guelphs (pro-papal) and Pope Boniface VIII – who all vied for control of the city-state. The White and Black Guelphs formed out of a feud between the Cerchi family (White Guelphs) whose wealth came from commerce, and the Donati family (Black Guelphs) whose wealth was linked to the nobility and the Church of Rome (“Dante's Inferno Canto 1”). In 1294, an event occurred that had a profound effect on Dante. Following Pope Celestine V’s abdication, Benedetto Caetani, a canon law scholar who had quickly ascended the church hierarchy, became Pope Boniface VIII. Boniface's papacy focused on consolidation and expansion of church power, asserting in the papal bull Unam sanctam that the pope was both the spiritual head of Christendom and superior to the emperor in secular matters ("Dante's Inferno Canto 19"). However, Dante, as a member of the ruling White Guelphs, believed that the pope and emperor should be co-equals with distinct spiritual and secular roles ("Dante's Inferno Canto 19"). As tension within Florence grew, Dante travelled to Rome to argue Florence's case before Boniface. However, in Dante’s absence and under the guise of peace-making, Pope Boniface sent Charles of Valois, a French prince, along with a papal army to Florence to overthrow the White Guelphs. While still in Rome, Dante was banished from Florence into exile and never returned to his native city.

In Inferno 6, Florence is the true protagonist of the canto - “la città partita” (the divided city) [Inf.6.61] full of “superbia, invidia e avarizia “ –“le tre faville c’hanna i cuori accesi” (three sparks that set on fire every heart / envy, pride and greed) [Inf.6.74-5] (Barolini Inferno 6 7). Dante damns the Florentines whose hearts were turned against each other to this circle of hell because they acted on those vices (the “sparks”) which inclined them to commit sinful acts ( the “fire”) (Barolini Inferno 6 15-19).

In this first artwork for Inferno 6, therefore, Florence itself takes center stage, represented by the Baptistery and the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore. In Dante’s time, only the Baptistery was standing as it had been consecrated in 1058. Construction of the cathedral had started in 1296, and was completed in the early 15th century. In the artwork, therefore, Dante has his back to the cathedral as he would never have had the opportunity to see it fully built.

Putting the cathedral at the centre of this artwork also symbolically represents Dante’s suffering at the hands of the church. Using cryptic language, Dante damns those members of the White and Black Guelph parties, as well as Pope Boniface VIII, who appeared to have had “minds bent towards the good” (“ch’a ben far poser li ‘ngegni”) [Inf.6.81], but in truth, “ei son tra l’anime più nere” (they are among the blackest souls) [Inf.6.85]. Highlighting the cathedral in this artwork underscores the major role that Pope Boniface had in betraying Dante and the city of Florence.

Dante's hatred for Boniface is so great that, in Inferno 19, Dante casts Boniface into hell before the pope even dies. By doing so, Dante disregards the theology of repentance, which allows sinners to repent up to their last moments of their lives. (Barolini Inferno 19 21) Dante is well aware of this doctrine as he vividly portrays late repentance leading to salvation in Purgatorio 5 (Barolini Inferno 19 21). Here instead, Dante denies Boniface free will and the opportunity to seek forgiveness and salvation during the last few years of his life (Barolini Inferno 19 21).

In this artwork, the air “filled with cold, / unending, heavy and accursed rain” (de la piova / etterna, maladetta, fredda e greve) [Inf.6.7-8] is rendered in a dark purple colour. The “shadowed air” (“l’aere tenebroso”) [Inf.6.11] of this canto mirrors the upheaval and suffering Dante felt due to his exile from Florence, as well as the violence that befell his beloved city.

The red-orange colour of the earth held by Virgil pays homage to the “terra rossa” in the southern part of Tuscany, near Siena (the modern-day colour “Sienna”). Iron ore and ferric oxide in the clay of the region were used during the Renaissance by Tuscan artists such as Vasari and Caravaggio to add a tone of deep red to the brown in their paintings (“Sienna”). Unfortunately, by the 20th century, the natural resources in Tuscany were depleted (“Sienna”). The colour of the earth in this artwork symbolizes the destruction wrought by domination and power: just as the Black Guelphs and the Pope dominated Florence and banished their innocent opponents, the Tuscan land was similarly dominated by relentless clay mining, leaving the land depleted and abandoned.

(N.B: In the title of my artwork, the verb gittare (modern day: gettare) reflects Dante’s poetic and archaic language, in line with the literary style of the Commedia.)

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Barolini, Teodolinda. “Inferno 6: The City that Stuffs its Sack.” Commento Baroliniano, Digital Dante. New York, NY: Columbia University Libraries, 2018. https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/dante/divine-comedy/inferno/inferno-6.

Barolini, Teodolinda. “Inferno 19: Whoring the Bride.” Commento Baroliniano, Digital Dante. New York, NY: Columbia University Libraries, 2018. https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/dante/divine-comedy/inferno/inferno-19.

"Dante's Inferno Canto 19." Dante's Worlds, University of Texas at Austin, https://danteworlds.laits.utexas.edu/textpopup/inf1901.html.

"Dante's Inferno Canto 1." Dante's Worlds, University of Texas at Austin, https://danteworlds.laits.utexas.edu/textpopup/inf1002.html.

"Sienna." Winsor & Newton, https://www.winsornewton.com/en-ca/blogs/articles/sienna.